On October 4, 2013, Vanessa Fontaine’s worst nightmare came to life. Despite having warned her autistic son’s school that he was prone to wandering, her son ran right out the door of his classroom – past cameras and a security guard – and vanished.

On October 4, 2013, Vanessa Fontaine’s worst nightmare came to life. Despite having warned her autistic son’s school that he was prone to wandering, her son ran right out the door of his classroom – past cameras and a security guard – and vanished.

Her son Avonte’s remains washed up from the river three months later.

In May of 2014, a nine year old autistic child from Bellevue, Nebraska, left school – unnoticed, surprising –and frightening–his mother by walking in the door and asking for a snack. Her son functions at the level of a 5-year-old and crossed two busy streets to get home, with no understanding of how to do so safely.

Again, in May of 2014, another nine-year-old child on the autism spectrum left his Oakland Park, Florida school early and walked 12 blocks home. He was found trying to get into his home through a window and later described chatting with a complete stranger along the way.

These aren’t the only incidents of autistic children wandering from school (commonly referred to as “elopement”).. Following such stories, we usually hear school districts “express concern” and pledge to “work with parents to ensure their child’s future safety.” I’m sure they mean it and will probably try. But what do they say to mothers like Vanessa Fontaine? Her son’s school can’t work with her now.

The vast majority of U.S. schools do not have an autism elopement protocol. It’s not because they can’t afford it; an effective protocol like the one I will propose here is mostly free. The reason schools don’t have one is simple — they don’t realize they need it.

In the not-too-distant past, many students on the spectrum would have attended special needs schools. Such schools usually have a depth of experience with elopement. But mainstream schools usually do not. Inclusion has been a big thing in American education, with autistic students now attending class now with their typical peers. However, these students do not always have the support they need. Teachers and staff rarely receive autism-specific training. Human beings make mistakes. Doors get left open. And, in the chaos and panic of discovering a child is missing, bad split-second decisions are made in the absence of an effective plan.

Today, one in 68 children is diagnosed with autism. Statistically, half of them will elope, and more than a third cannot effectively communicate their name, address, or phone number. (An even higher percentage will struggle with communication beyond this.) And autistic children are often drawn to water. Of the children who are found dead as a result of elopement, 91 percent will be found in water.

If a school district’s plan to address autistic elopement is merely to wait for it to happen and call police, they are planning for tragedy.

After consulting with members of law enforcement, here is a protocol I’m suggesting to my child’s school district. I’m calling it The SPECTRUM Alert for Schools. The important thing to remember is that this alert/code will necessarily look different for each school. To be effective, it must be planned by individual schools based upon their location, size, design, proximity to water, etc. The SPECTRUM Alert is not a ready-made plan, but a roadmap for designing one .

S (Search grid) In conjunction with law enforcement, the school and surrounding community should be mapped out on a search grid. If the school is fenced in, there should be a perimeter walk to determine any areas vulnerable to elopement. From there, the grid should expand outward a mile or two, taking into account any and all bodies of water, dangerous intersections, train stations, parks, playgrounds, etc. School personnel not directly supervising students should already know and have practiced reporting to their assigned search areas. Note: Water should always be searched first. No matter what.

P (Pre-identification) Each child prone to elopement should have on file a Quick Reference Sheet. This should be compiled by the school with the assistance of parents and possibly personnel who have worked with the child previously. It should contain the following information:

1. Child’s identifying information

2. Presence of GPS tracking technology

3. Current photograph

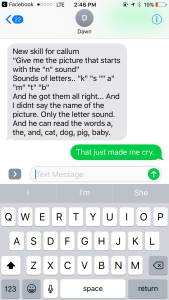

4. Child’s current level of communication

5. Child’s documented interests, behaviors, preferences, aversions, etc.

6. Health considerations

7. List of possible locations the child might go within the search grid

E (Law Enforcement liaison) One person’s job should be to call law enforcement immediately. This should happen while the search begins – not following it. In addition to contacting 911, this is the person who should contact parents immediately. The liaison could also commence activating a “phone tree” already set in place by parents. That phone tree might include friends, family, and neighbors willing to assist a search. The child is likely to know these people well and may respond to them more easily.

C (Code) Typically, schools have alert codes. In my district, they are based on colors and represent different emergency situations. Students and staff know how to respond to each code. A code should be called on the intercom. This will keep students out of the way of the search party. Teachers should be instructed to quickly look into the hallway and out windows and alert the office if they see the child in question. In upper grades, it might also be possible to have students assist in a search in teams on school grounds.

T (Training) All school personnel and school resource officers should receive training in autism. Such training can often ward off elopement incidents to begin with. That training should include information in sensory integration disorder, social difficulties, literal thinking, common triggers for meltdowns and elopement, law enforcement considerations, food aversions, bullying and autism, self-stimulation, and more. It would be a good idea to consult an organization like CARD (there’s usually one in your area) and a behavior analyst in planning this training. A 15-minute after school meeting isn’t going to suffice.

R (Relationships) Law enforcement, school personnel, and school resource officers should be encouraged to develop positive relationships with autistic students, who are often very literal in their thinking and may fear the police, based upon what they may have seen on TV. Classroom visits in non-emergency situations should occur so that in an emergency ,these children will not fear police and jeopardize their recovery. As soon a child prone to elopement enrolls at the school, the faculty and staff (including cafeteria workers, bus drivers, etc.) should be notified. They should see the child’s photo and learn his or her background information.

U (Understanding) Common triggers that distress students on the autism spectrum should be understood by all staff, including substitute teachers and volunteers. By stressing the Understanding component of this plan, schools can often avoid the situations that might prompt an autistic student to elope from school. Because special events in gyms, auditoriums, and cafeterias are often painful to the senses of autistic students, there should be a careful plan to avoid subjecting these children to trauma. A trigger for elopement could easily go unnoticed in the chaos of an activity day. This component is the most powerful part of this plan, though the least understood if effective training of staff doesn’t occur.

M (Media) Radio, television, and social media are powerful when it comes to locating missing children. A media strategy should be considered by the school district and law enforcement for use with autistic elopement situations. Facebook would be a particularly useful tool in small cities.

Ideally, the SPECTRUM Alert will not be confined to the school. Local law enforcement could enhance this alert system by allowing special needs families to pre-register a vulnerable child with the department in the event of a wandering incident outside of school. Schools with personnel that could be made available to police departments for autism training would make this even easier.

The SPECTRUM Alert protocol would cost a school district little to no money. Most of it involves planning with personnel already on the payroll. It’s simply a matter of a school making the choice to plan for an elopement incident and putting it into practice.

Human beings are by nature inherently optimistic creatures. We tend to go through life not prepared for the worst out of a self-protective need to believe it won’t. But schools cannot afford to do this with regard to autistic elopement – any more than we can afford to not prepare for fires, tornadoes, or armed intruders on campus. As educators, are in loco parentis. It’s the prime directive for our profession – to do for our students what we would do for our own children. Including the most vulnerable ones –like mine.

It’s time for every school district in this country, without delay, to adopt a SPECTRUM Alert for Schools.

Like this:

Like Loading...

When you’re raising a typically-developing child, eventually they stick to their own beds and no longer sneak in to cuddle. There comes a time they don’t want that constant touch. It’s bittersweet. But it’s okay, because you assume that one day they’ll have that need met again when they partner off.

When you’re raising a typically-developing child, eventually they stick to their own beds and no longer sneak in to cuddle. There comes a time they don’t want that constant touch. It’s bittersweet. But it’s okay, because you assume that one day they’ll have that need met again when they partner off. A couple of weeks ago, I listened to a conversation between parents of autistic children. The first – a mother and father – were relating their experiences as parents of a severely autistic, nonverbal child with intellectual disability and discussing how they love, enjoy, and accept their son as the person he is.

A couple of weeks ago, I listened to a conversation between parents of autistic children. The first – a mother and father – were relating their experiences as parents of a severely autistic, nonverbal child with intellectual disability and discussing how they love, enjoy, and accept their son as the person he is. Every now and then, I come across articles giving suggestions for interacting with parents of special needs children. Usually, they’re written by an educator or a special needs parent and are well-meaning. But I’ve noticed that they’re usually missing something. Either they don’t have a clue what special needs parents go through or need. Or they don’t have a clue what the real life of a teacher is like or the precarious position they are operating from when advocating for students and advising parents. So, the suggestions are incomplete because they’re either unrealistic or coming from a place of not knowing.

Every now and then, I come across articles giving suggestions for interacting with parents of special needs children. Usually, they’re written by an educator or a special needs parent and are well-meaning. But I’ve noticed that they’re usually missing something. Either they don’t have a clue what special needs parents go through or need. Or they don’t have a clue what the real life of a teacher is like or the precarious position they are operating from when advocating for students and advising parents. So, the suggestions are incomplete because they’re either unrealistic or coming from a place of not knowing. A few weeks ago, I received a heartfelt private message from a mother who is just confronting her young son’s likely autism diagnosis. She had read a

A few weeks ago, I received a heartfelt private message from a mother who is just confronting her young son’s likely autism diagnosis. She had read a  3. I immersed myself in learning about the IEP process,

3. I immersed myself in learning about the IEP process,