Every now and then, I come across articles giving suggestions for interacting with parents of special needs children. Usually, they’re written by an educator or a special needs parent and are well-meaning. But I’ve noticed that they’re usually missing something. Either they don’t have a clue what special needs parents go through or need. Or they don’t have a clue what the real life of a teacher is like or the precarious position they are operating from when advocating for students and advising parents. So, the suggestions are incomplete because they’re either unrealistic or coming from a place of not knowing.

Every now and then, I come across articles giving suggestions for interacting with parents of special needs children. Usually, they’re written by an educator or a special needs parent and are well-meaning. But I’ve noticed that they’re usually missing something. Either they don’t have a clue what special needs parents go through or need. Or they don’t have a clue what the real life of a teacher is like or the precarious position they are operating from when advocating for students and advising parents. So, the suggestions are incomplete because they’re either unrealistic or coming from a place of not knowing.

I’ve had the unique experience of sitting on both sides of the IEP table. I’m both a veteran teacher and the parent of a high needs child with nonverbal autism. And that gives me insight that’s both helpful as well as painful. It’s difficult to sit in on an IEP now – either my own child’s or someone else’s – knowing what I know. I want to jump in and say things that might not be welcome. I want to fight for services I know there is little money for. I want to bang my head on the table, knowing all too well how what I’m hearing will come across to the child’s parent. I want to lash out, because I know when I’m being “handled.” I know, because I’ve been – and am – in their shoes, both the educators’ and the parents’.

Here is what I wish my colleagues knew about how to forge positive relationships with parents of special needs students:

- Assume nothing. Over the years, we meet a lot of parent types. And like everybody else, we tend to categorize them. We quickly infer whether they have an education, are likely to help their children with homework, or if they know anything about their child’s disability. We then react or condescend accordingly. Be careful about that. I’ve met highly educated parents who know little about their child’s differences. And I’ve known poor parents with terrible grammar and threadbare clothing who’ve researched their child’s condition tirelessly. People will surprise you, so make no assumptions based on appearance, community standing, or diction.

- Understand that the child you work with isn’t the child they live with. You’re seeing just a snapshot of that child in an environment that can be stressful, unfamiliar, and unforgiving. The child you believe to be distant may be quite loving at home. The child you believe won’t communicate at all may very well communicate with his siblings. Remember that no one is the same in all settings. Not even you. Once you learn what a child is capable of outside of school, work to create a similar comfort level in the school.

- Give them a chance to talk. Special needs parenting can be a lonely affair. While friends are posting about baseball wins and science fair prizes, our children’s successes aren’t easily appreciated by all. But parents of children with disabilities have the same need to brag on our children, to voice our fears, and to soak up all the little stories you can share with us. It matters. And this meeting with you may be the only chance they have all year.

- Ask for their insight. Just because they might not be fluent in educational or therapeutic terminology (or they may be), it doesn’t mean they don’t have unique insight into their child. Listening to how the child functions at home and in the community can inform how you approach instruction, behavior management, etc. There’s no lab quite like living with a child with a disability. Respect their experience, and benefit from it when you can.

- Reward their child. Often, special needs kids aren’t recognized in front of their peers and their community. This is defeating to everyone. The students need their accomplishments celebrated. Even if they aren’t cognitively capable of understanding the award being given, everyone can benefit from applause now and then. Peers need to learn to appreciate different kinds of success. Parents need a moment to feel proud and take pictures. Our communities can always use a smile. Don’t forget your special needs students when it comes time to celebrate. You may have to come up with creative and unusual rewards. But do it. And do it up big.

- Give the gentle nudge, and then walk the first step with them. If you want the parent to register with an autism center, special needs athletics, or a parent support group, take it one step further beyond merely mentioning it. Facilitate an introduction, if possible. Send a link by email. Ask for a flyer and personally hand it to them. Sometimes the daily life of a special needs parent is overwhelming. You intend to do things, but other stuff gets in the way. If you can, help them get started in things you think might benefit them and their family. It might be just what they need but don’t quite have the energy to initiate.

- Offer support services for their other children. Alicia Arenas gave a wonderful TED Talk about “glass children” – the children of special needs siblings. These kids have their own needs that are often unmet. They may go years without ever being able to speak to anyone who knows where they’re coming from. Start a support group for siblings of disabled students right in your school. Give them a place to share their experiences. This will support the entire family and earn you brownie points with parents who worry just as much about their typical kids – but, by necessity, must focus more attention on their siblings.

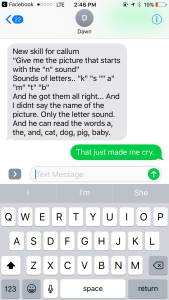

- Surprise them with positive emails and text messages. It’s funny how many school districts frown upon this sort of thing. But they’re foolish to do so. There is nothing that will put a parent in your corner quicker than to send random positive pictures and texts home. I don’t have time to talk on the phone. But a text in the middle of my day showing him participating in circle time with a “He did ____ today!” melts my heart to goo. A teacher or aide taking time to do that convinces me he’s loved – which will go a long way to forging positive parent-school relationships. Learn how to use the little emoticons and apps that will cover other kids’ faces from the photo and text happy things about your students. It’s a sound investment.

- Help their peers to interact with and understand their children. Teach acceptance. Talk about differences. Start a lunch buddy program. Read stories aloud that will foster empathy. Push, cajole, and fight for the emotional well-being of their children in school. Not only will this do much to increase parents’ confidence in the school, it will have a direct impact on the child’s school performance.

- Tell them the truth. If you know that services they want for their child will not be approved by higher-ups, do not lie and say they are unavailable in your school. Technically, there is no such thing as “not available” – if a student with a disability requires it to learn. Tell the parent to call for an IEP meeting, make your recommendations to the staffing specialist/ESE director/principal, etc., and make the higher-ups address the request. Yes, advocating for students and not incurring the wrath of administrators is a balancing act. But by playing a part in dishonesty, you are ultimately perpetuating the cycle of students in your district not getting needed services. And that’s not why you became a teacher.

IEPs and some interactions with special needs parents aren’t always fun. Lack of funding and awareness are to blame – although the system pits parents and schools against one another. But it doesn’t have to be that way. My son’s IEP team laughs, shares cute stories, celebrates successes, speaks honestly about expectations and struggles, and generally functions beautifully. But that didn’t happen magically or overnight. In the end, positive school-parent relationships are key. Invest in that, and you invest in both your students as well as your own happiness as a professional.

A few weeks ago, I received a heartfelt private message from a mother who is just confronting her young son’s likely autism diagnosis. She had read a

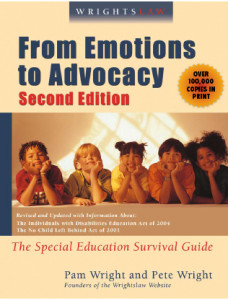

A few weeks ago, I received a heartfelt private message from a mother who is just confronting her young son’s likely autism diagnosis. She had read a  3. I immersed myself in learning about the IEP process,

3. I immersed myself in learning about the IEP process,

Disclaimer: This is about my particular child and my own experiences raising a child with autism. I am not attempting to represent the autism parenting community with this post. As the saying goes, “It’s a spectrum.” Yes, I already know that our situation is far better than some. And, yes, I know that our situation is less encouraging than others. Which is true about most things in life, I suppose.

Disclaimer: This is about my particular child and my own experiences raising a child with autism. I am not attempting to represent the autism parenting community with this post. As the saying goes, “It’s a spectrum.” Yes, I already know that our situation is far better than some. And, yes, I know that our situation is less encouraging than others. Which is true about most things in life, I suppose.  1. My son can tolerate much more than I gave him credit for. He sat, happy as the proverbial clam, and just…enjoyed the ride, man – enjoyed the ride. If I turned and caught his eye or called his name, he’d just turn and smile…all the way to his eyes. I swear I fell even deeper in love with my child during those hours on the road. He is a likable little dude. He handled museums, crowds, unfamiliar restaurants, my mother’s annoying Jack Russell terrier, hotel rooms, and a rather amusing and startling exploding bath in a Jacuzzi tub. Knowing how many of our kids in the ASD community struggle in being overwhelmed with sensory issues, I recognize his tolerance of the world around him as one of his strengths. And, for his sake, I’m so grateful for it.

1. My son can tolerate much more than I gave him credit for. He sat, happy as the proverbial clam, and just…enjoyed the ride, man – enjoyed the ride. If I turned and caught his eye or called his name, he’d just turn and smile…all the way to his eyes. I swear I fell even deeper in love with my child during those hours on the road. He is a likable little dude. He handled museums, crowds, unfamiliar restaurants, my mother’s annoying Jack Russell terrier, hotel rooms, and a rather amusing and startling exploding bath in a Jacuzzi tub. Knowing how many of our kids in the ASD community struggle in being overwhelmed with sensory issues, I recognize his tolerance of the world around him as one of his strengths. And, for his sake, I’m so grateful for it. 2. I think my NT daughter is acting out for attention. Having viewed

2. I think my NT daughter is acting out for attention. Having viewed 6. My husband is a great daddy. Of course, I knew this already. But time and proximity have a way of making you less aware of what you already know. He is equally involved in everything. He goes to doctor appointments, attends therapy, gets up in the middle of the night, checks school folders, and accepts our son for who he is. No parent is perfect, but his children are very aware of how much their daddy loves them. And I know I’m not in this journey alone.

6. My husband is a great daddy. Of course, I knew this already. But time and proximity have a way of making you less aware of what you already know. He is equally involved in everything. He goes to doctor appointments, attends therapy, gets up in the middle of the night, checks school folders, and accepts our son for who he is. No parent is perfect, but his children are very aware of how much their daddy loves them. And I know I’m not in this journey alone. 8. As the song says, we have a long way to go and a short time to get there. The only way to do it is to take it one mile at a time. To look back at our progress , while keeping our eyes on the road. To, while certainly using the road maps of those who have gone before us, remain aware of sudden detours and unexpected holdups.

8. As the song says, we have a long way to go and a short time to get there. The only way to do it is to take it one mile at a time. To look back at our progress , while keeping our eyes on the road. To, while certainly using the road maps of those who have gone before us, remain aware of sudden detours and unexpected holdups.